Concern for AI – part 1

“AI is intrusive, nefarious, deceitful, indefensible, intentionally difficult to unprogram and uncaring of one;s personal privacy. I want no part of it.” -G.

In response to this statement about AI posted by my neighbor on our community list, I spent several days diving back into the foundation of my Masters degree in Applied Mathematics, Evolutionary Computation Applied to Radio Astronomy. My thesis included development of Karoo GP, a Genetic Program that I trained to isolated radio noise caused by human made machines from the desired astronomical sources generated by the MeerKAT array, South Africa. Later, the same code was applied at LIGO to isolate false triggers, also generated by the noise of the thousands of parts of the interferometer.

I have been following the rapid uptick in application of Generative AI in the past two years, and often speak about it with my colleagues in software development. This is an incredibly complex topic, with an incredible array of potential, positive outcomes. At the same time, there are many serious, negative implications across all layers of society, world-wide.

For my neighbor and our community I provided a foundation for a conversation, as most people have little to no understanding of how machine learning applications give foundation to neural networks, deep learning, and now generative AI, nor why we even “need” machine learning in the first place, and what function it serves in a modern, data-driven world.

While I have not been working at the code level of machine learning for some time, and I do not claim to be an expert in artificial intelligence, I maintain a working understanding of the underlying systems, which I share with you here.

IN THE BEGINNING

Humans have since the time of the Egyptian, Greek, and Roman empires recorded and analyzed data to improve farming, manage the finances of complex social systems, and to study the star lit heavens. Since the industrial revolution, advances in medicine, manufacturing, and the study of human and natural systems have made more important the need to reveal patterns in the data we collect.

Early computers were mechanical devices (1800s) followed by electronic computers (mid 1900s) capable of calculations far faster than the human mind. But why is a computer necessary, let alone artificial intelligence?

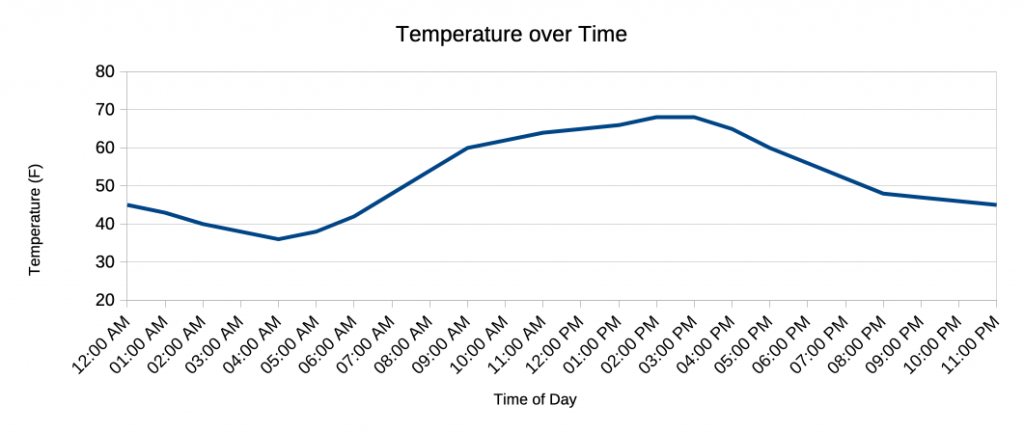

Let’s consider a small data analysis problem, the time of day incremented in hours, and the temperature outside measured in degrees, such that we desire to plot this as an [x,y] graph, with time on the x axis and temperature on the y axis.

(sunrise to mid afternoon)

time = 7 am; temp = 48F

time = 8 am; temp = 54F

time = 9 am; temp = 60F

…(mid afternoon to sunset)

time = 6 pm; temp = 56F

time = 7 pm; temp = 53F

time = 8 pm; temp = 48F

… and into the night, cooling until sunrise and starting over again.

Image by Kai Staats

The plot presents a wave-like function. Day in and day out, over and over again as long as you kept placing dots on the graph, left to right, up and down. And we don’t need a computer to do this, just a pen, graph paper, and maybe a ruler to connect the dots.

Now, let’s add a third variable–the angle of the sun from zenith (overhead) such that we can track the time/temp correlation not just day to day, but month to month for one year. If we live north or south of the equator, we’d see an overall warming trend in the summer and cooling in the winter. This too we could do with a bit more graph paper and some patience for many more data points.

But if we want to build a formula to predict the temperature at any time of day, any week of the year, it gets more complicated. Perhaps something like:

temp = mean_temp + fd[cos(date)] + ft[cos(time)]

where we have converted both time and date to circular (cosine) functions so that we can employ the rise and fall of the sun. The function “fd” and “ft” are coefficients that convert time to temperature. This is harder than our original plot, but yes, it’s still something we can do by hand if we have the time and gumption.

This application of mathematics to the natural world is at the very core of science, since the earliest observations and predictions. The goal is to understand the underlying function of everything from plant physiology to human metabolism, from animal migration to stellar evolution in a galaxy far, far away.

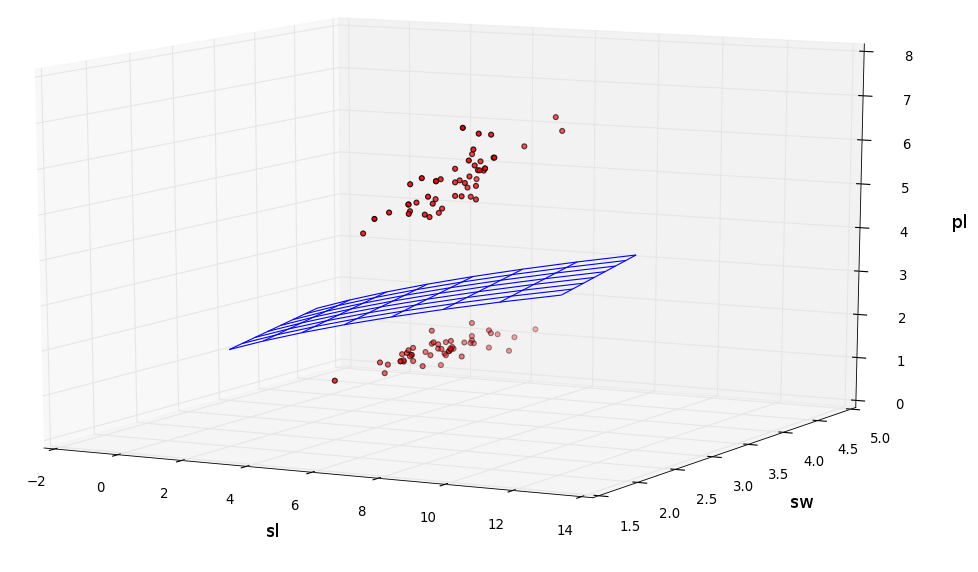

A great example of this kind of mapping of the natural world is the work done by Dr. Fisher in the 1930s whereby he applied measurements of the sepal length and sepal width, petal length and petal width of 150 flowers across four species of iris, as acquired by Dr E. Anderson. This is referred to as the iris flower data set. Fisher then hand-developed a formulae into which he (or anyone) could apply the measurements of one of the four species studied, and without seeing the plant, determine the species through formulaic classification.

Image by Kai Staats

The iris dataset has become a defacto standard that all machine learning programs are expected to solve, including my own. For example, with the following formula derived by Karoo GP, we can accurately assess the type of iris between any two species with 100% accuracy:

sl = -sw + pl2

It gets a bit more complicated when solving for one of three species, but the same concept applies. There are countless millions of examples of statistics (mathematics applied to data analysis) in our modern world–measuring the physical, chemical, biological, or psychological parameters of a given function, from the behavior of online shoppers in holiday seasons to Netflix views, from cancer cell growth to weather prediction–statistics seeking correlation, and often causation.

THE JOY OF DISCOVERY

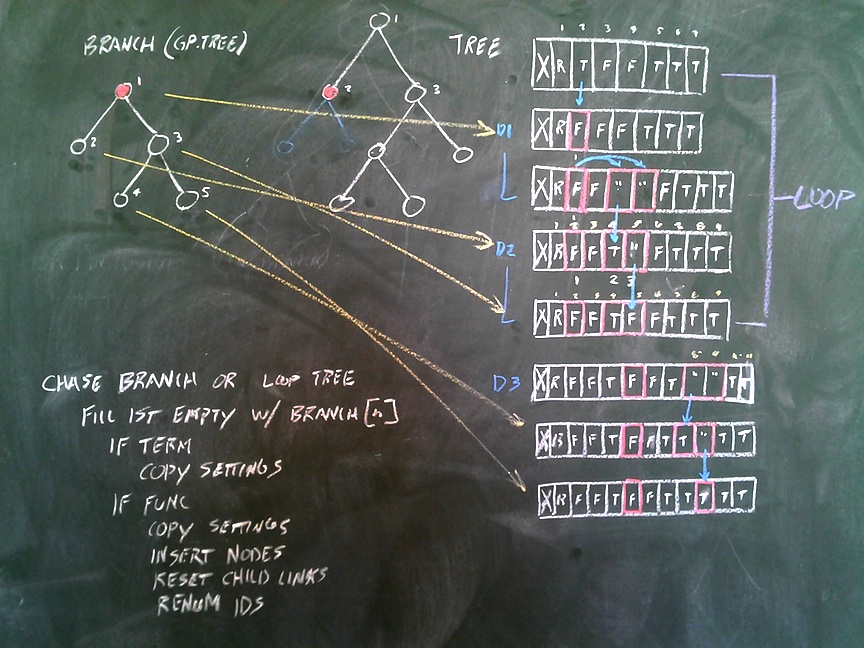

Image by Kai Staats

Discovery of patterns, in any field, is not some sterile activity conducted by socially inept geeks in white lab coats (well, maybe sometimes), but a rigorous process that follows a centuries old practice of a) generating a hypothesis, b) developing an experiment, c) collecting and analyzing data, d) comparing to the hypothesis, and e) sharing both the results and methodology to the world, then refining the experiment and doing it again (more often than not) to improve the model and more importantly, the understanding of the natural process.

This can lead to an increase in healthy habits, reduction in car accidents, and discoveries of breathtaking beauty. For me, for the many times in my work I have been part of pattern discovery, I find myself with an accelerated heart rate and deeply satisfying sense of peace. Something as simple as seeing the growth rate of a pea plant correlated to the amount of carbon dioxide provided (as we do at my worksite with each experiment in bioregeneration) is incredible. It’s repeatable. It’s demonstrable. And it’s a means to seeing inside a small piece of the cosmos and unraveling its mystery, not to dissect or control, but to understand and marvel at its inherent beauty.

I share this because beyond the profit driving many of the companies hosting chat bots and AI driven tools, there are a body of programmers that for the past two decades have enjoyed the discovery that comes through the iterative improvements to their underlying code. I understand their joy and motivation, even if I am increasingly concerned with the way in which their code is being used.

I will never forget the moment when my machine learning code Karoo GP evolved and re-discovered Kepler’s law of planetary motion based on the same numbers recorded by Newton more than 300 years ago. I ran through the halls of the astrophysics institute where I was based, shouting “It worked! It worked! It really worked!” I can only imagine what it was like for Newton, based on his own observations, to discover patterns that defined thermodynamics, the age of the Earth, and gravity all in one lifetime.

IT’S ALL STATISTICS

Back to our comparatively simple effort to predict the temperature each day across the seasons, we will find ourselves with a pattern based on a general formula (above), but not close enough to truly predict with any accuracy, especially not in this new world of rapidly shifting climate functions. It takes far, far more sophisticated models to predict with any accuracy at all.

So we add “degrees of freedom”, additional variables to present more facets of the weather functions. We might take into account the annual increase in greenhouse gases such as water vapor, carbon dioxide, and methane; dust from fires and volcanoes, a reduction in reflectivity by shrinking polar caps and snow mass on glaciers; desertification of once fertile regions, even the 11 years solar storm cycle, to name a few (and there are thousands more).

But now we have far more variables than just time of day and angle of the sun–too many to plot on a piece of paper. And the relationship between these variables cannot be visualized in the human mind nor found by hand. So we need help.

At the foundation of machine learning are statistics and regression analysis.

Statistics we all understand to some degree, as every day we process statements such as “flying is __ times safer than driving”, “smoking a pack of cigarettes each day increases your chance of lung cancer by __ percent”, and “Four out of five dentists recommend brushing your teeth.” (not sure what’s going on with that 5th guy ?!$).

Statistics gives us skills in critical thinking, making important decisions, and managing our finances. It’s a powerful set of tools that should be a required class in high school. I did not learn how to apply statistics beyond an average high school vocabulary until working on my masters degree at age 44. I learned to apply the basics (mean, median, and standard deviation) to build simple relationships between data points prior to training a machine learning algorithm. These “features” offer first order correlations that boost the machine learning algorithm’s ability to find more meaningful relationships between variables in the dataset.

Regression analysis is the development of a mathematical function (e.g. x = 2y + z) to represent the relationship between two or more raw data points or features, as given in my simple temperature prediction model (above), the work of Dr. Fisher with iris flowers, to millions of everyday examples:

Predicting the Popularity of Social Media Posts

Predicting House Prices

Predicting Exam Scores Based on Study Time

Forecasting Sales for a Business

Predicting Sports Performance

(More at Geeks for Geeks.)

In my work at LIGO to isolate black hole mergers in the noise of the complex machine, we regularly engaged in processing 4,000 variables (4,000 columns in a spreadsheet) with 10,000 data samples (rows). Yet, this is a “small” dataset in just about any modern data environment.

LACK OF TRANSPARENCY

Now, the start of my answer to G’s question–there are important distinctions between statistical analysis, machine learning, and AI.

As I began, with traditional statistical analysis we, the human, are manually or semi-automatically building the formula, by hand or with a spreadsheet or the application of advanced statistical formula. But as any insurance company will tell you, just having data and applying a model does not equate to an accurate prediction. Far from (else, our insurance rates would be going down, now up).

The data may have been highly skewed when captured, based on who collected it (student vs industry professional), where it was collected (rural Kansas vs downtown LA), and who was paying for the data (university, pharma, or politician). The algorithms might have been generated by employees who have long since retired or an old system that is now considered antiquated.

ChatGPT is harvesting data from across the entire world, pulling from sources that are genuine and those that are completely bogus. Yet ChatGPT is opaque to how or where it acquired the data it is processing, and how it generated the result.

When I was at LIGO there were fierce battles between the astrophysicists as to whether to trust machine learning to classify a celestial event, or to rely on older, more transparent computer models. My code was unique in that it was 100% transparent, with every line of code commented and the outcome being a mathematical expression built from known input variables.

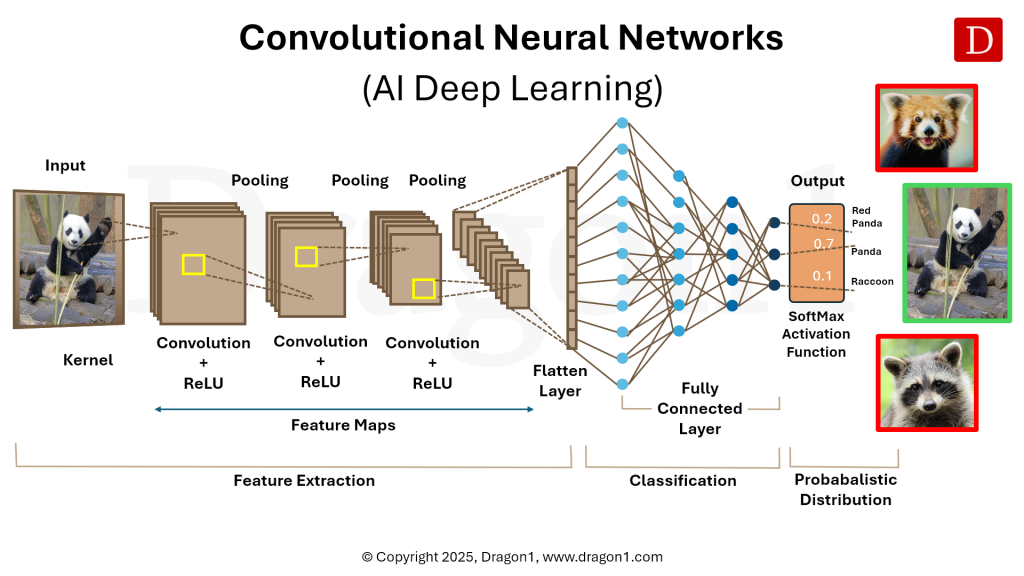

Image by Dragon 1

On the other hand, Convolutional Neural Networks, the foundation for Deep Learning and now Generative AI, are far more complex, the feature generation and determinant processes a relative black box, opaque to the exact means by which a classification or decision was made.

Convolutional neural networks (“neural nets”) can process tremendous arrays of data, systems so incredibly complex that any other process would require many stages to arrive to a similar conclusion, if at all. Neural nets can be trained on tens of millions of labeled photographs, bodies of text, and data.

However, neural nets and now Generative AI are black boxes, meaning, you cannot see inside. Therefore you have little to no idea how they arrive to their conclusion. And that is the problem.

While AI is already being applied to cancer research, protein folding, weather prediction, self-driving cars, and understanding who is likely to become homeless based on variables captured in routine visits to the health clinic–no one can tell you, precisely, how the solutions are generated internal to the AI itself.

IS AI INTELLIGENT?

No. At least, not yet. It is a powerful data processing engine that can rapidly read, review images and videos, process and respond via both written and spoken language, and in many ways appear to have human responses, even conversations.

But at the core are a series of probability curves, potentials for a or b, c or d, and so on until the image of the panda is the most likely label applied (see image). And if I ask a chat bot to fill in the blank, “I am so hungry I could eat a ______”, another set of probabilities built on a global dataset of thousands of similar sentences, on-line references, suggest that the most likely outcome will be “horse”.

In many ways, this is how we process language too, and how cliche phrases propagate as we automatically pull responses from a deep well of potentials. We quote celebrities or a comedic one-liner from a film. We get stuck on a particular phrase for days, even months at a time until that critical path is dislodged and a new “training” opens a new pathway through our brain. And sometimes we say really stupid, even mean things “that we didn’t mean to say” because we didn’t actually think about it—it just came out. Well, that’s just a statistical fill-in-the-blank that requires very little cognition, often spurred along by emotion (which thankfully, ChatGTP does not yet have). If we truly thought about each and every thing we said, we would say very little at all.

Maybe what intrigues (and scares) us about AI is that in the reflection of this powerful thing we have birthed, we might not be all that intelligent after all–just a moist, gooey collection of cells and organs and gray matter that most of the time is not terribly self-aware. Just like ChatGPT.

This concludes Part 1 …

In part 2 I will provide guidance for how to reduce your exposure to AI, and a general guide to on-line security. In the mean time, learn more about how ChatGPT works.