History

It doesn’t take a physics lab full of PhDs to find simple solutions to complex problems. Sometimes we need only look to other parts of the world and what they’ve been doing for centuries. All along the Mediterranean coast homes are painted white with limewash or whitewash to reflect the intense sunlight, keeping the interior of the homes cool. In Iceland, they do the opposite, building with black roof tiles to absorb solar heat.

The modern (with lab and PhDs) version of whitewash is Purdue University’s world’s whitest paint. Developed by Purdue professor of mechanical engineering Xiulin Ruan, this new paint is fighting global warming by keeping surfaces cool to reduce the need for internal air conditioning. According to Ruan and his team’s models, covering 1% of the Earth’s surface in their technology could mitigate the total effects of global warming, a fact encouraging them to continue pursuing formulas suitable for surfaces like asphalt and roadways.

Our Home

Colleen and I have spent the past year mitigating the increasingly warm summers by reducing the amount of thermal energy our house gains during the day, and increasing the amount of thermal energy released at night.

It is important to note that our home is a rather unusual construction, not at all ideal for anywhere but the temperature climate of San Diego or coastal Hawaii. That said, it came with the property, provides exceptional views of the surrounding wildlife year-round, and is enjoying a successful remodel toward thermal mitigation.

It is important to note that we live at 3000 feet elevation with winter, night lows dipping into the mid-20s with days at 50-70F. Summer will see three months in the mid-90s by mid-afternoon with a few weeks over 100F, sometimes pressing 110F. With each summer night, even on the hottest day in the year, the air cools to the low 70s or high 60s. This is the way the desert is suppose to be, and was until the introduction of concrete, asphalt, and air conditioning (which we will address later).

Too hot to touch?

Our first major effort in thermal mitigation was painting the roof white. As with most of the homes in this southeast Arizona region, galvanized sheet metal is a preferred material as it lasts, with minimal care, thirty to fifty years.

However, as anyone who has touched sheet metal in the Arizona sun knows—it gets really hot—dangerously hot. When you touch but cannot hold your hand to the surface for the intensity of the heat, you have reached your ‘threshold of pain‘. This is the minimum temperature at which your body feels pain and you have a natural reaction to remove yourself from that situation. This varies from person to person, and from object to object. 110F air is tolerable while a 110F Jacuzzi will require some getting used to. We can generally hold our hand to or walk barefoot on 110F concrete. But if that temperature climbs to 120F or 130F, it becomes unlikely you will stand there for long. I use 132F as my own threshold of pain for what I can tolerate with bare feet or my hands.

In the course of our work on our home, we have used an infrared thermometer which has been compared to both a mercury and bi-metalic coil thermometer and validated to within 2 degrees Fahrenheit. This gives us a high degree of accuracy up to twenty, even thirty feet away.

Our house is built such that our roof extends over the outer walls by 4 feet. This casts needed shade in the summer, and with the low sun in the winter allows direct sunlight to enter our home and heat the concrete floor through the large, double-pain windows.

With the infrared thermometer we are able to measure the temperature of the metal roof from the underside of the overhang such that as we painted each section, we could readily determine the effect of the new paint application with the same ambient air temperature and immediate solar gain.

Choosing the right paint

There are many brands of paint on the market today. Most of the products are now water-based (acrylic), moving away from oil-based to reduce toxic chemicals consumed (and wasted) in manufacturing. While acrylics have come a long way, and make sense for bedroom walls and refinished desks, nothing beats the durability and weather resistant nature of a good oil-based stain or paint.

At my work at Biosphere 2 I became familiar with the oil-based Rust-Oleum brand Rusty Metal Primer. My team found it to be an incredibly durable product, readily applied with brush, roller, and sprayer. The Gloss White top coat is far more reflective of solar radiation than an elastomeric, and without the need for pressure washing every six months to keep it from collecting dust and losing its reflectivity.

Rust-Oleum will tell you that you need to use a special, water-based primer to adhere to galvanized metal. However, my test proved otherwise—a screwdriver only marginally able to scratch the primer after 24 hours drying. This is likely due to the fact that the metal roof on our house is nearly thirty years of age, with the galvanized metal losing its sheen.

In July 2023 we worked from 4:30 am ’till 7:30 am three mornings in a row to apply the primer. Due to our work schedules we returned to the project a week later and applied Rust-Oleum High Gloss White, again with an airless sprayer. With just one coat we achieved a quality finish (a second coat will even the highs and lows). We painted the two main sections (north and south) that together encompass more than three quarters of the total surface area. This [2024] summer we completed the east section of the roof with one day of prep and two days painting (primer and white respectively). The west end remains.

When complete, the total number of gallons of paint for our 1500 sq-ft roof will be 7 gallons primer and 7 gallons white. At $37 per gallon that is roughly $500 in paint. A new roof of the same size would be between $10-30,000 for materials and at least double for labor, if contracted.

From 153F to 115F

Using or infrared thermometer we were thrilled to discover that we reduced the surface temperature of the galvanized steel from ~150F to ~110F (actual high temperature ranges between 135F and 153F; with the underside low ranging from ambient air to 115F for the painted surface, corresponding to humidity, cloud cover, smoke particles, and time of day).

While we have 4″ foam insulation beneath the corrugated steel over 2″ tongue-n-groove pine ceiling, over the course of a day the heat eventually gets through. We used to feel the radiation (infrared) on the backs of our necks and bare arms despite the air temperature maintained at 80F with mini-splits, much in the way that a desert canyon wall will radiate heat after sunset.

Now, that radiant heat penetrating our home is reduced, the thermal gradient from ground level to the loft (20 feet) has been reduced to just ~5-8F degrees, which is 10F less than before the paint. Furthermore, in a comparison of May 2023 to May 2024, despite the 3F increase in average temperature, our electric bill went down $22. There are other factors, perhaps, but the point is—we are both feeling and seeing a difference.

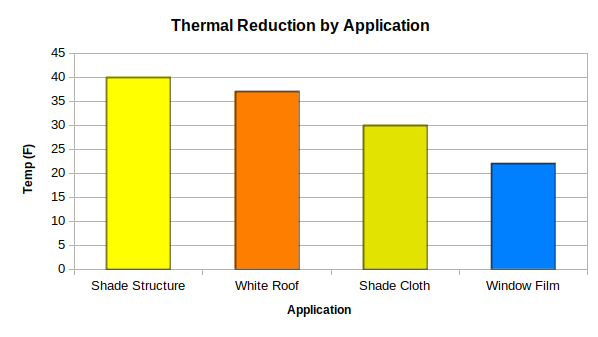

What we experienced first hand is confirmed in this and many other similar articles:

The surprisingly simple way cities could save people from extreme heat.

“New research suggests cities are ignoring the power of cool roofs at their own peril. A study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters earlier this month modeled how much cooler London would have been on the two hottest days in the extra-hot summer of 2018 if the city widely adopted cool roofs compared to other interventions, like green roofs, rooftop solar panels, and groundlevel vegetation. Though simple from an engineering standpoint, cool roofs turned out to be the most effective at bringing down temperatures.”